Clinic Secures Asylum for Celebrated Mexican Journalist

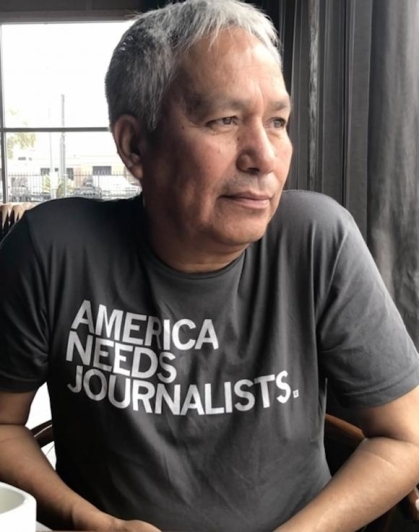

Emilio Gutierrez is an award-winning Mexican journalist, devoted father, University of Michigan Knight-Wallace Fellowship recipient, and National Press Club honoree. Thanks to the work of Rutgers Law School’s International Human Rights Clinic (IHRC), he is also a newly-minted US asylee, protected from ever being deported back to Mexico, where he was intimidated with beatings, home raids, and death threats as a result of his reporting on government and police corruption.

Gutierrez first became an IHRC client in 2018, when he was unlawfully jailed after a speech he made criticizing US immigration policy. IHRC filed a habeas corpus petition on Gutierrez’s behalf based on the First Amendment and international law, and secured his release.

“It was very clear that Emilio was being targeted for his criticism of the broken US immigration system,” says clinic director Penny Venetis. “We were able to convince a federal judge in Texas that his detention and imminent deportation had nothing to do with the merits of his asylum case, and everything to do with his critique of the US government.”

The judge’s decision to release Gutierrez from detention in 2018 was a significant win for free speech and asylum seekers, drawing the attention of international journalism organizations and news outlets alike. Still, the matter of his asylum needed to be resolved.

“The IHRC began working on Emilio’s appeal as soon as he was released from jail in 2018 because we strongly suspected, based on Trump administration emails we had obtained through a Freedom of Information Act request, that he would be denied asylum,” Venetis explains. “Unfortunately, we were right.”

In their appellate brief, Venetis and her team at the IHRC argued that Gutierrez was entitled to political asylum as a member of a recognizable group singled out for persecution: journalists. Indeed, the Committee to Protect Journalists says that more than 150 reporters have been killed in Mexico since 1992 by cartels and corrupt government officials alike, making it the most dangerous place for journalists to work outside of an active war zone.

This type of argument, typically leveraged for asylum-seekers who face persecution on account of race, religion, or nationality, opens the door for other journalists seeking asylum who don’t have a clinical program or the National Press Club behind them.

“Lawyers can use the decision issued in Emilio’s case to protect other journalists who are persecuted abroad and seek asylum in the US,” says Venetis.

In the meantime, this decision is life-changing for one man and his son, who first crossed the border into the US in 2008.

“It has been a long journey, and these past 15 years have been difficult,” Gutierrez said in a statement. “I hope that my case will shine a light on the need to protect those journalists in Mexico and around the world who are working and risking their lives to tell the truth.”